With one child dying from malaria every minute, Kirsty Tuxford examines the innovative financing mechanisms being employed to help fund the development of a malaria vaccine and pay for the distribution of life-saving medication

A record-breaking US$7.5 billion was promised to Gavi, the vaccine alliance, by donors at the biennial replenishment pledging conference held in Berlin at the end of January. According to Gavi, a public-private initiative founded in 2000 to enable access to vaccines for the world’s poorest countries, the new pledges will enable it to help countries immunise a further 300 million children, resulting in five to six million lives saved.

“Everyone who has contributed to saving the lives of others should be very proud,” declared Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, hailing the fundraising effort, which included first- time contributions from China, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

While the US$7.5 billion is great news for children in need of vaccines for polio, Japanese encephalitis, measles, meningitis A, rotavirus and yellow fever, which are all distributed by Gavi, there is still no vaccine for the millions of adults and children at risk from contracting malaria, almost 3.3 billion people, according to pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

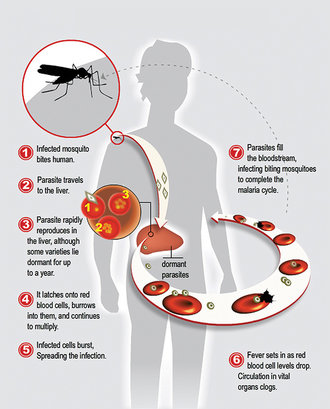

Malaria infects around 215 million people globally each year and kills more than 660,000, mostly children under five in sub-Saharan Africa. Worse still, in parts of Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand and Laos), the parasite from mosquito bites is becoming resistant to artemisinin, which is currently used to treat people infected with malaria.

In terms of financing delivery of a vaccine, Gavi’s Board agreed in November 2013 to consider support for a malaria vaccine if and when one is licensed.

“If there were suddenly a malaria vaccine, then Gavi would need to raise additional funds very quickly to roll it out,” says Paulo Sison, Gavi’s Director for Innovative Finance.

The search for a malaria vaccine

Such financing may be needed earlier than expected with two companies reporting successful trials of a vaccine. On the one side is Sanaria, a not-for- profit biotechnology company of 48 people, established in 2003 and operating out of Maryland in the United States. On the other, GSK, the multinational pharmaceutical company, with a US$23 billion turnover and a 30-year history of trying to develop a malaria vaccine.

It might not seem a fair race but Sanaria have two trump cards up their sleeve. First, they claim to have developed an effective malaria vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest form of malaria, which is currently undergoing rigorous trials; and secondly, despite their small size, their business model for raising finance is smart and dynamic.

“Directly or indirectly we have probably invested US$150 million in this vaccine,” says Dr Stephen L Hoffman, CEO of Sanaria. “We think we can get it out the door for another US$200-250 million. Our vaccine is designed to entirely prevent infection, so it would be good for you or me if we went on a safari, it’s good for the military, but what we’re really aiming at is to be able to immunise the entire population so we can stop transmission and eliminate malaria.”

The diversity of Sanaria’s funding partnerships is not in doubt. While the first funds came from the US in July 2003 with a small grant from the National Institute of Health of US$555,000 followed by US$30 million of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funds from the Institute for One World Health and PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, subsequent funding saw the company conduct a series of international trials paid for by local partners.

Having conducted the first vaccine trial in the history of Africa, funded by an African government, which was done in Tanzania with support from the Ifakara Health Institute, the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology and the Swiss Tropical Public Health Institute, the same thing has happened in Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Ghana and multiple clinical trials in the US.

“Sanaria is not paying for these trials, they’re being paid for by our collaborators,” says Hoffman. “We have 65 people scheduled to come to Tübingen in Germany in March as part of this international consortium to develop our vaccine, and we don’t pay for them to come. They’re all coming from Africa, Europe and the United States on their own dime. Our business model is a completely different model.”

Sanaria has worked with the Swiss State Secretariat for Education Research and the Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania; with the Kintampo Health Research Centre in Ghana and in Europe, with the Barcelona Centre for International Health Research, which funded a trial in Spain, and, in the UK, with the Jenner Institute, which funded a trial in collaboration with Sanaria.

“The vaccine and the regimen that we’re working on is highly effective, and we’re getting unbelievable input from our international colleagues,” says Hoffman. “Who we are not getting support from is big pharma, and some of the major donors.”

So why aren’t the big donors backing this?

“Most major pharmaceutical companies look at the results of malaria vaccine trials and the amount of money that has been invested and say no one’s proved that we can make a highly effective malaria vaccine,” says Hoffman. “But now along comes Sanaria and we have proved that a malaria vaccine is possible, but we’re manufacturing entirely differently from the big pharmas. We’re making a vaccine in mosquitoes. The others don’t have experience with this technology. They have tremendous expertise in overall vaccine development but not with our approach, so there’s nothing familiar about it.”

Sanaria states that the level of protection given by their vaccine is as good, or better, than the protection afforded by any vaccine for any disease on the world’s markets, and “far better than the protection afforded by any experimental malaria vaccine under development”.

“The problem I struggle with today is how do I meet my budget for this year?” says Hoffman. “Every day is a struggle, I can’t do the things I want to do as fast as I would like because of limitation of funds. That’s the flipside and we’re working to try to overcome that.”

Oil companies are taking an interest in funding, primarily because many of their workers are stationed in infected areas. In Equatorial Guinea, Sanaria is working in partnership with the government, Marathon Oil and Noble Oil to fund a clinical trial there.

Despite the challenges, Hoffman is optimistic about Sanaria’s vaccine. “Last year we had six trials and this year we have 14 trials,” he says. “We hope it will be on the market by 2018. It’s very exciting. The people in malaria know about it. There are still sceptics as there should be, and there are challenges to overcome but we are systematically getting over those thanks to the help of our partners.”

Although the latest figures show that malaria infections are falling–a 54 percent fall in mortality rates in Africa between 2000 and 2013–governments are hollering for the disease to be wiped out. Malaria- related illnesses and mortality cost Africa’s economy US$12 billion per year and in January, the African Leaders Malaria Alliance called for the elimination of the disease by 2030 at the African Union Summit of Heads of State and Government, which took place on 31 January 2015 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The big pharma approach Africa has been the centre of GlaxoSmithKline’s (GSK) efforts to test their malaria vaccine, RTS, S/AS01, which is designed to protect against Plasmodium falciparum and has been evaluated in a large clinical trial in seven African countries involving around 16,000 children. Recent data shows the vaccine can reduce the number of cases of malaria by up to a half in young children and by about a third in babies 18 months after vaccination. However, some previous trials did suggest that efficacy wanes over time.

One of the key challenges in malaria vaccine development is the complexity of the science involved. As Sophie Biernaux, Vice President of Vaccine Development, GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, explains: “Malaria is caused by a parasite rather than a bacteria or virus like many infectious diseases for which vaccines are largely available. Parasites are genetically very complex and can mutate. Finding a way to harness the immune system to target a moving target like malaria is challenging and there is currently no licensed vaccine against any parasitic disease.”

In July 2014, GSK submitted an application to obtain scientific opinion for the vaccine candidate with the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The submission will follow the Article 58 procedure, which allows the EMA to assess the quality, safety and efficacy of a candidate vaccine, or medicine for a disease recognised by the WHO of major public health interest, but intended exclusively for use outside the EU.

“If the EMA opinion is positive, the next steps would be to obtain a recommendation from the WHO as to whether or not the vaccine should be added to existing malaria control tools,” explains Sophie Biernaux, GSK’s Vice President, Vaccine Development. “This would pave the way for the vaccine to begin being used in national immunisation programmes in Africa. Because the vaccine could be used in some of the world’s poorest countries, we’ve committed to make the vaccine available, if it’s approved, at a not-for-profit price.”

Financing delivery of vaccines

If either or both of these vaccines get official WHO approval, then Gavi will look to fund distribution. The recent pledging conference was a success, but donations alone are not enough to fund Gavi’s vital work. Fortunately, Gavi has engineered some excellent partnerships that help to raise funds through bonds issued on the international capital markets by the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm).

IFFIm exists solely to finance Gavi, and does so by trading vaccine bonds in the capital markets, with the World Bank as Treasury Manager. The bonds do very well in the Japanese retail investment market (Uridashi bonds), where most of the buyers are Japanese women with US$1.2 billion raised there since 2008. “Housewives and vaccines have an emotional connection,” says Gavi’s Sison. “The investors know that the proceeds from buying the bonds go towards saving children’s lives. What has been helpful to IFFIm is that the World Bank knows the market quite well and has worked with a number of Japanese banks. Also, IFFIm has a very strong credit rating, currently AA or AA+, which makes it a very safe investment.”

IFFIm has begun to diversify its investor base–last November/December it launched its first Islamic bond issue (Sukuk). Eighty-five percent of orders for the US$500 million issue were from Islamic investors. Total IFFIm issuance to date since its foundation in 2006 has been US$5 billion.

Together, IFFIm’s donors, the UK, France, Italy, Norway, Australia, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden and South Africa, have pledged to contribute more than US$6.5 billion to IFFIm spanning 23 years. These funds are used to repay IFFIm bondholders. IFFIm was the first aid-financing entity in history to attract legally-binding commitments of around 20 years from donors and has transformed Gavi’s financial landscape, nearly doubling Gavi’s funding for immunisation programme, with contributions to Gavi totalling US$5 billion.

Investing in IFFIm provides investors with two main benefits. “First, the vaccine bonds are a safe investment with repayment supported by cash payments from sovereign donors to IFFIm and the conservative financial management of the World Bank,” explains François Lefebvre, Senior Financial Officer, Development Finance, at the World Bank. “Second, investing in these bonds saves lives. The bonds allow Gavi to purchase vaccines sooner than otherwise would occur, which gets the life saving medicine to the child sooner. Vaccine bonds are a socially responsible investment.”

Is IFFIm sustainable?

An evaluation, by London-based Health and Life Sciences Partnership in 2011, which was commissioned by Gavi at the request of the IFFIm board of directors, describes the model under which IFFIm operates as proven to be a low-cost, efficient way to help achieve the UN Millennium Development Goals by improving global health and achieving predictability in global health funding. The report also notes that IFFIm can be credited with saving at least 2.75 million lives.

The report goes on to state however: “IFFIm, in isolation, is not a sustainable funding model. Looking forward, Gavi has to face serious sustainability challenges as it aims to increase spending rapidly, at the same time as IFFIm disbursements, based on current donor pledges, are declining. These challenges were not created by IFFIm and are a Gavi wide issue but the IFFIm model, spending 20 years of donor contributions in five to seven years, makes them more acute.”

Sison says Gavi would like IFFIm to remain relevant and become a strategically important funding tool.

“But IFFIm’s ability to fund Gavi would naturally decline if nothing changes, that’s what the report was referring to when it said ‘unsustainable’, it doesn’t mean investing in IFFIm’s bonds would be riskier,” adds Sison. “We have to strike a balance where we accept that IFFIm’s funding isn’t as much today as it was in the past, though I would say that over the next five years, 2016-2020, IFFIm will still provide about US$1.2 to 1.3 billion of Gavi’s funds. It’s still significant. Between 2021-2025 funding will drop to just over US$500 million or US$600 million.”

Working together

The power of public-private- partnerships in the fight against malaria is evident. From the pharmaceutical companies such as GSK and Sanaria, which are manufacturing a vaccine, to the Gavi alliance of partners who work to distribute anti-malarial medication and other vaccines, it’s clear that the innovative financing combined with public donor funds is a powerful tool.

At the next Gavi pledging conference in 2017, malaria may be a catalyst to see donors once again committing larger amounts to IFFIm.

“If there is a vaccine that comes on the market that will require an acceleration of funding, for example, the malaria vaccine, then Gavi will be the agency that rolls out that vaccine, then that might be a reason for donors to add more funds to IFFIm,” says Sison. “Paying for a malaria vaccine rollout doesn’t have to be done all at once and donors would prefer to fund over a longer period of time.”